John Hamer spent more than 50 years in and around journalism. Most recently, he was President of the Washington News Council, an independent forum for media ethics that he ran from 1998 to 2015, when he retired. Hamer was formerly Associate Editorial-Page Editor at The Seattle Times. In 1984, The Times sent him on a trip to the Soviet Union to do a Travel section story on cross-country skiing in Russia. But he acted as an “undercover” reporter and also did stories about Soviet Refuseniks and the Communist system. After leaving The Times, Hamer became Senior Fellow at Discovery Institute and wrote a report on how to make Seattle a more internationally competitive city. He later became Vice President of the Washington Institute for Policy Studies, a statewide think tank, where he was co-editor of CounterPoint, a monthly media-critique newsletter. He also co-authored the "Watchdogs" media column in Seattle Weekly and Eastsideweek. He is a graduate of Dartmouth College and has a Master’s Degree in journalism from Stanford University. He lives on East Mercer Way right across the street from the JCC, and comes over to work out and/or “shvitz” regularly.

All words by John Hamer:

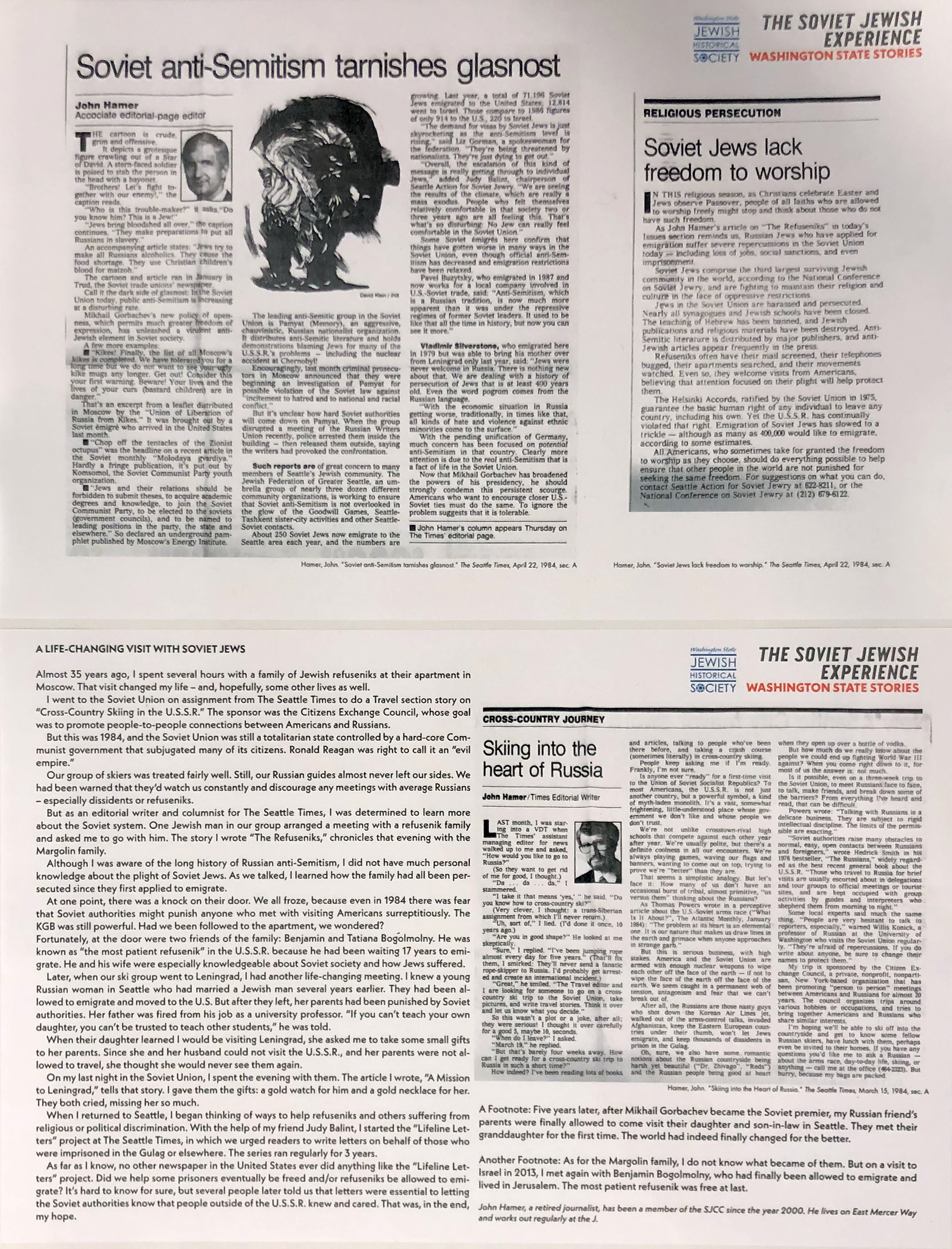

Almost 35 years ago, I spent several hours with a family of Jewish refuseniks at their apartment in Moscow. That visit changed my life—and, hopefully, some other lives as well.

I went to the Soviet Union on assignment from The Seattle Times to do a Travel section story on “Cross-Country Skiing in the U.S.S.R.” The sponsor was the Citizens Exchange Council, whose goal was to promote people-to-people connections between Americans and Russians.

But this was 1984, and the Soviet Union was still a totalitarian state controlled by a hard-core Communist government that subjugated many of its citizens. Ronald Reagan was right to call it an “evil empire.”

Our group of skiers was treated fairly well. Still, our Russian guides almost never left our sides. We had been warned that they’d watch us constantly and discourage any meetings with average Russians—especially dissidents or Refuseniks.

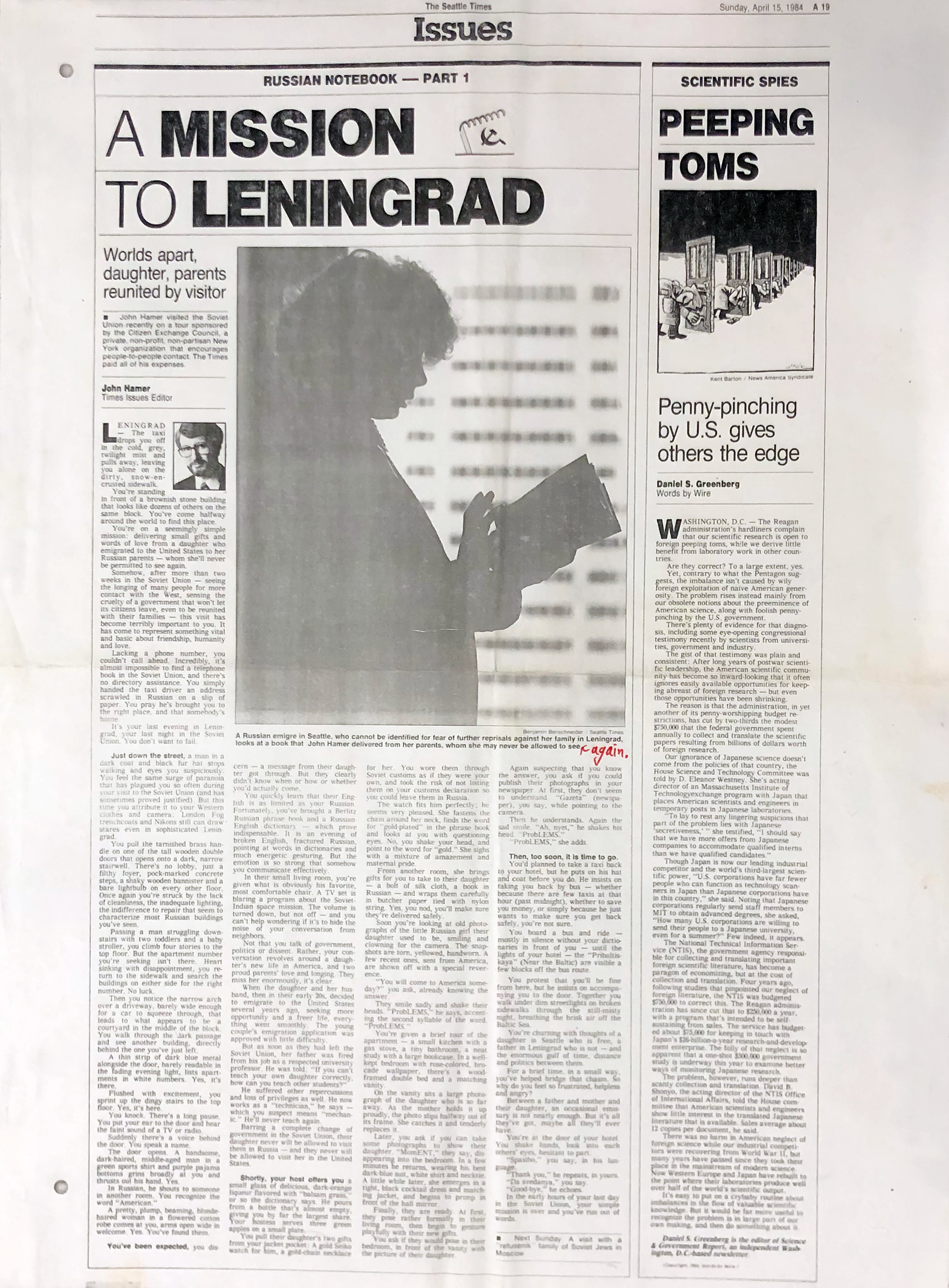

But as an editorial writer and columnist for The Seattle Times, I was determined to learn more about the Soviet system. One Jewish man in our group arranged a meeting with a refusenik family and asked me to go with him. The story I wrote “The Refuseniks,” chronicles that evening with the Margolin family.

Although I was aware of the long history of Russian anti-Semitism, I did not have much personal knowledge about the plight of Soviet Jews. As we talked, I learned how the family had all been persecuted since they first applied to emigrate.

At one point, there was a knock on their door. We all froze, because even in 1984 there was fear that Soviet authorities might punish anyone who met with visiting Americans surreptitiously. The KGB was still powerful. Had we been followed to the apartment, we wondered?

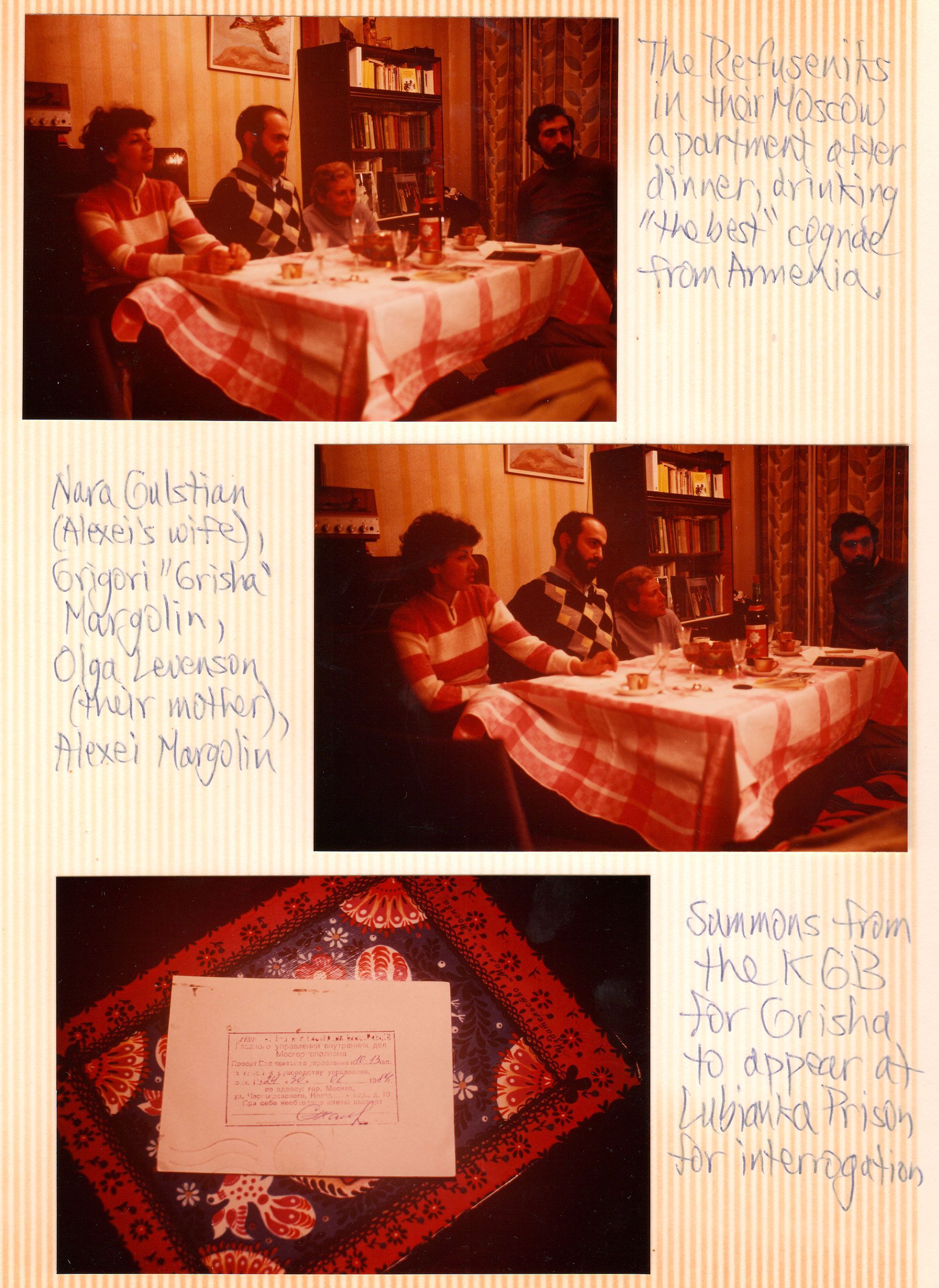

Fortunately, at the door were two friends of the family: Benjamin and Tatiana Bogolmolny. He was known as “the most patient refusenik” in the U.S.S.R. because he had been waiting 17 years to emigrate. He and his wife were especially knowledgeable about Soviet society and how Jews suffered.

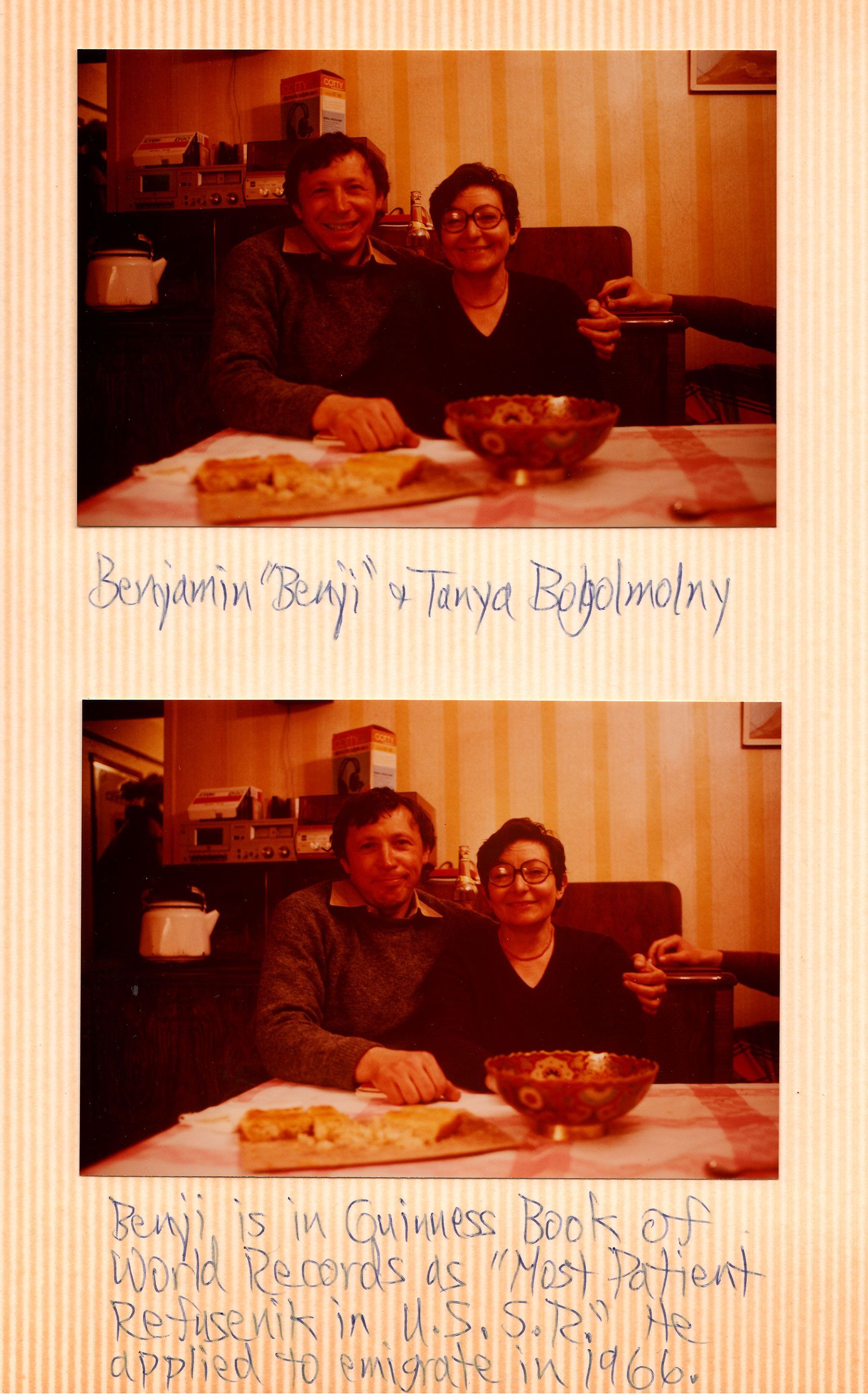

Later, when our ski group went to Leningrad, I had another life-changing meeting. I knew a young Russian woman in Seattle who had married a Jewish man several years earlier. They had been allowed to emigrate and moved to the U.S. But after they left, her parents had been punished by Soviet authorities. Her father was fired from his job as a university professor. “If you can’t teach your own daughter, you can’t be trusted to teach other students,” he was told.

When their daughter learned I would be visiting Leningrad, she asked me to take some small gifts to her parents. Since she and her husband could not visit the U.S.S.R., and her parents were not allowed to travel, she thought she would never see them again.

On my last night in the Soviet Union, I spent the evening with them. The article I wrote, “A Mission to Leningrad,” tells that story. I gave them the gifts: a gold watch for him and a gold necklace for her. They both cried, missing her so much.

When I returned to Seattle, I began thinking of ways to help refuseniks and others suffering from religious or political discrimination. With the help of my friend Judy Balint, I started the “Lifeline Letters” project at The Seattle Times, in which we urged readers to write letters on behalf of those who were imprisoned in the Gulag or elsewhere. The series ran regularly for 3 years.

As far as I know, no other newspaper in the United States ever did anything like the “Lifeline Letters” project. Did we help some prisoners eventually be freed and/or refuseniks be allowed to emigrate? It’s hard to know for sure, but several people later told us that letters were essential to letting the Soviet authorities know that people outside of the U.S.S.R. knew and cared. That was, in the end, my hope.

A Footnote: Five years later, after Mikhail Gorbachev became the Soviet premier, my Russian friend’s parents were finally allowed to come visit their daughter and son-in-law in Seattle. They met their granddaughter for the first time. The world had indeed finally changed for the better.

Another Footnote: As for the Margolin family, I do not know what became of them. But on a visit to Israel in 2013, I met again with Benjamin Bogolmolny, who had finally been allowed to emigrate and lived in Jerusalem. The most patient Refusenik was free at last.