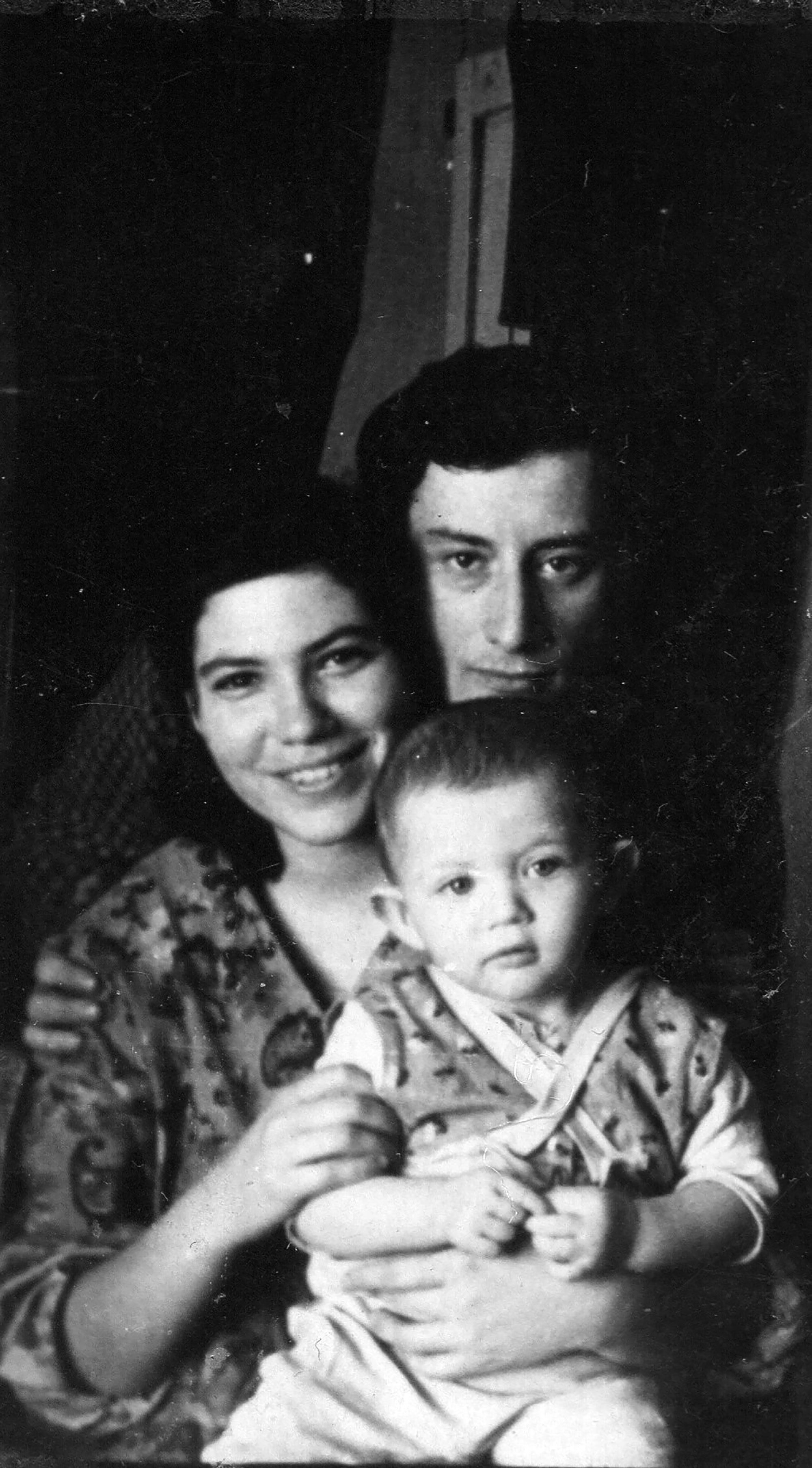

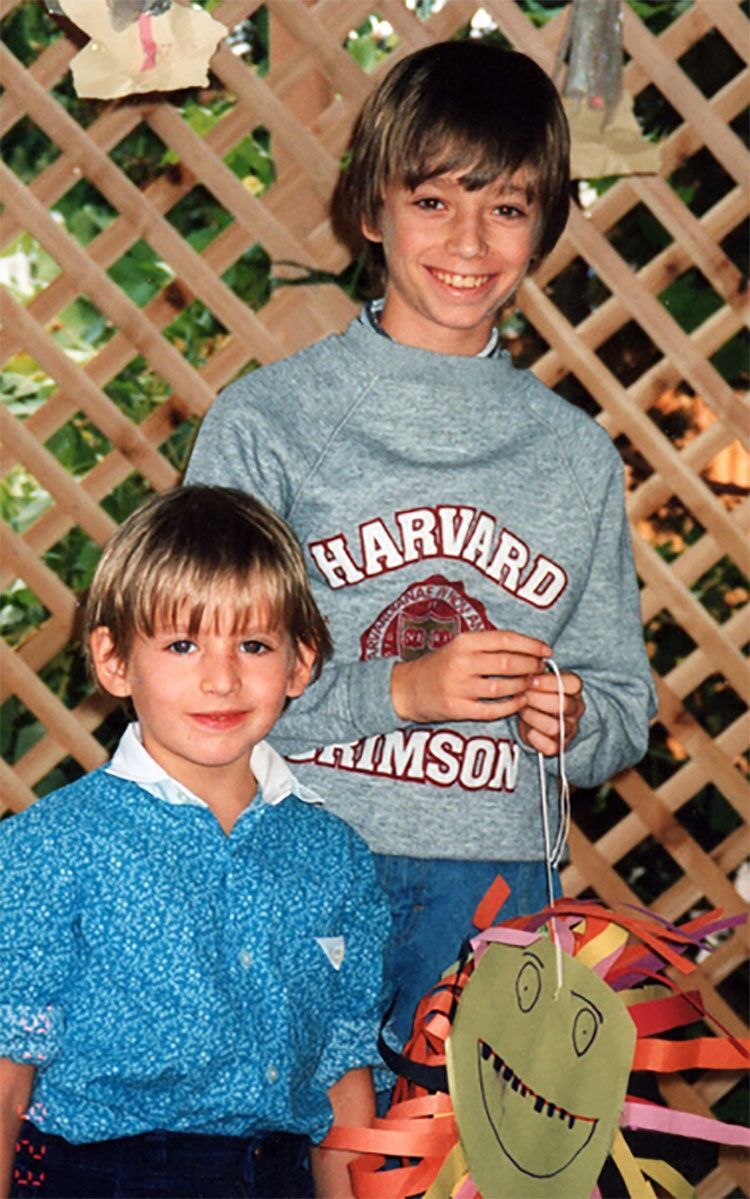

Husband and wife Gregory Korshin and Bella Pozina emigrated to the United States in 1991, near the end of the Soviet era, with their two sons, ages twelve and five. They grew up in the city of Kazan, the capital of the Republic of Tatarstan, in the 1960s. By Soviet standards, it was a middle class existence in a region that was relatively tolerant of Jews, if not Judaism.

“There were no synagogues open in my time,” says Gregory. “There was no Jewish life in our time, until 1986, 1987. Jewish things were just forbidden. Actually I taught myself Hebrew and I was the first teacher of Hebrew in Kazan in over two generations. I had always wanted to learn it, but there was no sources to learn. And then suddenly I found a photocopy of a textbook in Hebrew and I taught myself within a few months and then started teaching others. Many people were in great love with Israel then and we were also considering our options.”

He tells his story in a matter-of-fact tone, but it sounds anything but to American ears. His mother had two master’s degrees, in mathematics and electronics, and attended the Kazan Aviation Institute, while his father had a degree in law. “But because he was the son of an enemy of the people, he was prohibited from pursuing a career in law. Because my grandfather was repressed. He was killed in Stalin’s time. He was chief engineer of a huge explosives factory somewhere in Ukraine, in ’36 or ’37, but things were different then, because in Stalin’s time if you said something wrong then the next day you were killed. And there was some sort of incident in the plant while my grandfather went to get the Order or the Red Banner or something in Moscow and he was never seen again. And my grandmother with the children they were kicked out of their apartment. It was very typical. Bella’s father was almost killed in the Gulag too.”

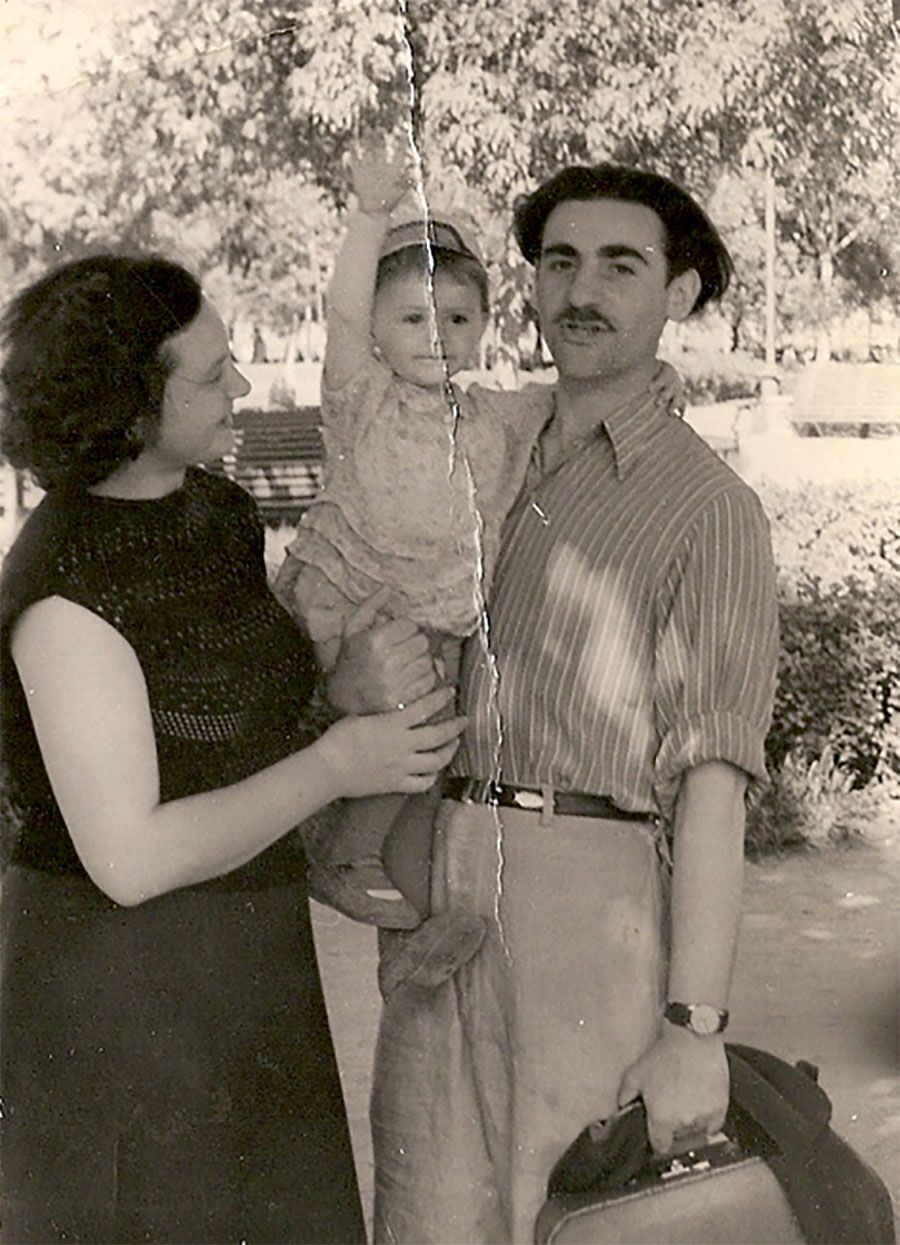

Insulted for being a Jew in the army, Bella’s father fought a duel, and though no one was killed he was court-martialed as a Zionist terrorist. “Fortunately for him,” Bella explains, “at that time, people who had a real cause, committed something real, they were getting less time than the people whose crimes were in the imagination of the persecutors, these people would be told they were spies or criminals or something.”

“He behaved as an officer,” Gregory continues, “to defend his honor. And the court martial understood that. There were three judges and one judge said he should not die for it.” Bella’s father was 21 years old. “He was sent to the gulag in the far east where people would just die left and right. And he survived. He never wanted to talk about this. He wanted only to mention that sometimes when it was spring and there were salmon runs and they caught fish, they just sucked the blood out of it. There was no question like, let’s do barbecue or something. It was just like, oh there’s food, let’s eat it now.”

“And in that place,” Bella says, “it was so harsh, very few people survived there. Then after Stalin’s death he was released.”

Gregory continues, “People here, we have grandsons now and my children and grandchildren also have grandfather and grandma. Many in my generation never had any grandfathers. They were killed in Stalingrad [during World War II] or died in the gulag. Mostly there were grandmothers. Rarely there were grandfathers.”

The idea of emigrating was with Gregory from an early age, long before such a thing was possible. “When I was a student in high school or the university, I had already started thinking that the Soviet Union is not the place for me. I felt strongly about being Jewish and getting out. I was a little bit of a closeted Refusenik, but it was never actionable, just because of the circumstances. My parents lived in an enterprise-owned apartment, and a lot of enterprises were connected somehow with the military. Most of the industry was defense related. So the thing was if you want to quit and say, I want to go to Israel, then you are kicked out from your apartment, because the apartment does not belong to you. It belongs to the enterprise where you work. And therefore my parents didn’t want to do this.

“Although my father was not allowed to pursue his career in law, and Bella’s father was in the gulag, they were not bitter people. They were happy people living in Kazan. Kazan was a very developed city. You can travel. If you don’t ask too many questions, if you don’t express your personal political opinion, you are fine by Soviet standards. Of course you have to stand in line for eggs, and they had coupons to buy meat, crazy things, but you can get by. In fact Kazan was not the place from which Jews would immigrate. Throughout my years before the whole huge immigration started at the end of the 1980s, Jews from Kiev, from Ukraine would move to Kazan.

“My first experience with Judaism [as a religion] was when my father suddenly died. It was two months before we emigrated. I already was fluent in Hebrew, we were absolutely Jewish, but religion was not part of being Jewish. It was prohibited. Of course, there were semi-secret places where old Jews would get together for a minyan. So when my father died, I felt I should do something. For Americans, yes, being Jewish means it’s a religious aspect. For us it’s more ethnic; more tribal I would say. Kind of positively speaking. Being in the same boat. It was really people who could trust each other.

“It is a sense of belonging,” Bella says. “You don’t have to say anything, you just do it. You see a person and you know you belong together.”

“In the United States,” Gregory says, “I do not think there is as strong a group feeling, tribal feeling. In Russia, you recognize this guy and you understand each other instantaneously. You are in the same boat. Because you are different, you don’t want to be like everybody else. I didn’t want to be like Russians.”

That sense of Jewish identity is still an essential part of life for Gregory. “Am I secular? Yes. Am I religious? Yes. I don’t know. I don’t have an answer. I know that I study the Torah every day, just because I like studying it. Do I go to the synagogue? Well, sometimes I do, but not very often.”