I was born and raised in Seattle. Sephardic family on both sides. My paternal grandmother, Dora Levy, was actually the first Sephardic woman to arrive in Seattle in 1906. There was hardly any community here—there were just under 20 people at that time. She spoke five or six languages, so she was very involved in resettling people when they came. She was very much a part of the community as it grew. The Sephardic culture was very much a part of my growing up. Ladino was spoken in the home by my grandparents and aunts and uncles. They would go to that language when they didn’t want the children to understand, so it became very important to understand what was being said. As we grew up, a lot of the words and things we held on to and used throughout our lives, but not in coherent sentences.

Interest in Spanish and Sephardic history

I think all that background pushed me to a Spanish major in college. I went to the University of Washington and majored in Spanish Language and Literature. I spent two years in Madrid; I was at the University of Madrid for a year, and I went to New York University in Madrid for another year, but I ended up graduating from the University of Washington. I mastered modern Spanish and saw all the ties to the Ladino, which was an older version of Spanish. As things progressed I came home, got married, had children. The Sephardic life was very much a part of our home as well—I’m also married to a Sephardic—so that was a bit unusual. But as things progressed, there was a growing interest in the Sephardic culture; about five or six years ago, there seemed to be this upswing of interest. A group was formed and ended up going to Spain sort of as a “roots” trip, and saw a lot of our culture there. We founded the Seattle Sephardic Network upon our return. Our mission was to include all Sephardics and to incorporate things that they might enjoy: things that are cultural, music, food, things that are of interest, and for us to be open to the whole community, to be an organization in the community that isn’t one synagogue, or another synagogue, but a place where everyone can come enjoy and celebrate the culture. What’s going on worldwide seems to show this renaissance that’s happening. Spain and Portugal are offering citizenship. That was very important to me, not only because of my ties to Spain, for which I felt a very strong affinity from the beginning, from when I first went there at age 19. I moved forward to apply for my citizenship to Spain, and I’ve actually received it. It was a process, but one that I felt very fulfilled by. I was one of the first ones to go through it, and I’ve helped countless others that are beginning the process. We have an organization at the University of Washington that gives the exams—you do have to take two exams for the citizenship—and there are only four places in the US that give those exams, one of which happens to be in Seattle [the Cervantes Institute]. So, we filter a lot of people through here.

One of them is a language exam and the other is a culture exam about Spain. It is all in Spanish. When you take your language exam, part of it is oral; part of it is written. For the cultural exam, there’s a study book like you’d study for a driver’s license. I went through the process and have been helping others. I’ve gotten involved in organizations that are encouraging that sort of interest in the Sephardic community. There’s an organization in Spain called the Red De Juderias, which is an organization that promotes a network of cities that have Jewish (Sephardic) heritage. This year I was made the US Ambassador to the Red de Juderias of Spain. Portugal is also offering citizenship. They don’t have exams to take, but you do have to show a little bit more of lineage, which may be difficult to do, to go back to the 15th century. So, I’ve been involved in all that. There is also an international conference every two years called Erensya ["Heritage" in English] for Sephardic communities held in different cities around the world, to bring them all together to learn from each other. And in 2019, the Erensya conference will be coming to Seattle, which will be the first time in the U.S. I lobbied hard for it, and it will be very exciting for Seattle. It’s about 25-30 different Sephardic communities that will come to Seattle to share information and network.

In tracing my Sephardic heritage, I’m sort of an anomaly in the sense that my family’s been here since 1906. They were a part of the Sephardic community and they could trace it, as they’d been involved in synagogues from then. So, it wasn’t a difficult thing for me to prove, since my family had been part of the community from the beginning. For others, it’s a little bit more difficult. But oftentimes, they’ve been able to go back to their grandparents or great-grandparents that were members of a synagogue somewhere and try and trace it back from there. If you don’t have that it’s very difficult—you’d have to hire a genealogist, and that’s not so easy. Finding the records is also difficult. My husband’s mother’s maiden name was Polícar, and there is a small town in Spain named Polícar. We went there, and I thought, “You know, this might be something worth investigating.” Well, Polícar is so small that there’s not even a restaurant there. We did find a bar where we tried to question people, but their records—if there are any—are in a larger city center of a region. And you also have the First World War and the Second World War and the Spanish Civil War to contend with, so it’s close to impossible.

I grew up in a household where both sides were Jewish, the grandparents were Jewish; the whole idea of values of education and family were very much ingrained in our lives. I was an observant family member, not Orthodox. Our synagogue was Orthodox, but we were never Orthodox. We observed all the holidays. My father’s family was the dominant family here—he had three other brothers and two sisters—and everybody was here in Seattle, so we always got together with them. My mother’s family was from Portland, so that wasn’t as much a dominant part of our lives during the holidays. But we observed holidays always. Two nights, you know, Sephardic style. But not Orthodox by any means—much more cultural, which I find is the same for a lot of Sephardics. The strengths that they feel about being Sephardic is the cultural part of it, as well as the religious. I grew up in South Seattle, and there were lots of Jewish people in South Seattle, in Seward Park and Mount Baker. Because of that, those around us were used to our holidays and what we had, and so we were able to maintain the culture and the values that we had at home, without feeling like we had to assimilate into something else. It was never an issue.

The specifics of being Sephardic

I think you can differentiate Sephardic people in much the same way that you would differentiate somebody from Northern Europe versus Southern Europe—very demonstrative, openly affectionate, noisy family gatherings. I think it’s much more of a Mediterranean personality versus a Northern European personality. That is a very dominant feel within the Sephardic families—more open, not as reserved, and in many ways more tolerant, I feel. I think that if you took a religious Ashkenazi Jew and a religious Sephardic Jew, those two Orthodox Jews would appear a bit different, mostly because of their backgrounds. And I think there is an adaptability. Maybe that comes from being a minority culture within the Jewish community; for that, you need to adapt and be a little less rigid to survive.

I think when you look at it, it is a very male-dominant culture. But I would say that almost all households are matriarchies. I think that the place of the woman in the home is a very strong one, and the woman’s place in the family is a strong one. And because the family is so important within the Sephardic culture, that role is a dominant one. I think that the female plays an incredibly strong role in the Sephardic culture. Clearly, as I go back to my grandmother—on my paternal side, it appeared that my grandfather was a strong character and I think he was a wonderful, warm guy, but I think that ultimately it was a matriarchy. He died much younger than my grandmother did, so she carried on, but I think she managed the house and six children and volunteer work very well.

I grew up with a grandmother who was, to me, the first feminist. She came on her own at 17; she was the first one of our family here. She was educated and spoke five or six languages. She believed that women could do anything and that they were very bright, and that no one should tell them differently. And she would portray it all the time, and she used to say, "If you want something, go get it: It’s yours to go get." She had a very broad world vision, which I think was very helpful to me growing up. It wasn’t a Sephardic vision, or a Jewish vision, or a Seattle vision; it was much more of a worldly vision. She worked outside the home as a volunteer: she donated her time, she resettled people. And she had six children. She managed it all, and she did it with a strength that—you never had any doubt that she was capable or incapable of doing something: It was that she was capable. And she always used to say, "Never wait for someone else to make you happy; you make yourself happy first." And she had two daughters. Neither one married early in life, and so I grew up with not only this strong grandmother, but two aunts who had careers. So, my influence from a young age was probably from a very different vantage point than others in the community.

Real estate and volunteer work

I sell residential real estate, and I have for 29 years. I do it here in the Greater Seattle Area. I’ve loved it from the beginning. It has lots of new people, and it’s a new challenge all the time, which I like. And it’s flexible, so it gives me time to be on other boards and get involved. I am involved in, as I said, the Seattle Sephardic Network. I’ve been involved with Hillel, with Jewish Family Service, and Juvenile Diabetes. Each one is sort of a section to enhance and to enrich, for me.

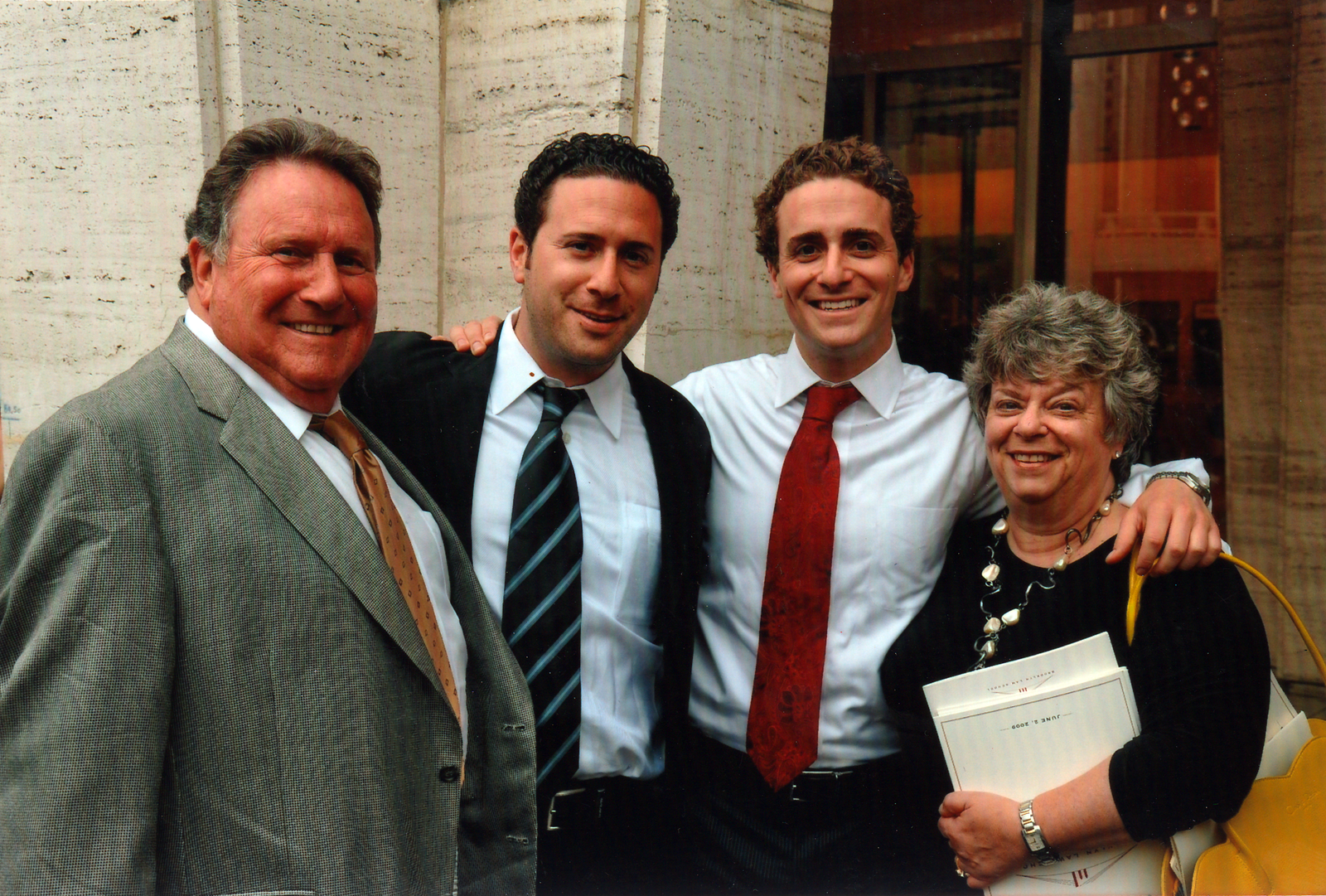

I have two grown boys. My oldest, Loren, is married with two girls and a boy, and they live in Seattle. And I have a younger son, Mitchell, who lives in Northern California. Both are doing very well—very close, we’re all a very close-knit family, which is very important to us. We have a good time together, and we work at it. It’s important. My husband Joseph is from Seattle as well. Both of his parents are from here, and he has a brother who lives here on Mercer Island. He works for the Benaroya Company and had worked on their real estate for a long time, so very involved here locally as well. He’s involved in the Seattle Sephardic Brotherhood, so our ties to the community are strong on both sides.

Influential movements and people

My grandmother, as I said. She was a very strong figure, and she’s probably even to this day the wisest person that I’ve probably ever known. She was able to sit back and look at a situation and understand it. But I think that one of the things that was very big in molding me and in the continuation into life was being a child of the '60s. We had race relation issues, we had women’s issues, we had all sorts of things—and to see and to live through that, to try and put yourself in someone else’s shoes, to fight for that—I think that being that person in that point in time of history was big for me. And the Jewish values of kindness to others, the education, and the significance of family are all important to me. I think one of the things that I work at is empathy. We live in a world where things are moving quite quickly. We’re very lucky to have what we have, and we don’t always take the time to realize that we need to have a little empathy, and work toward those that don’t have as much. And that is not easily taught. I mean, you have to live it.

I went to Franklin High School, and race relations were a big issue. I can remember out of the U there were migrant worker issues. I think my father felt that I carried a soapbox on my back. My family wasn’t really political. But I had a great-aunt who was in Istanbul in the '50s, and things were getting difficult there. They wanted to bring her here, and it was very difficult at the time. There was a thread there of people getting a little political to see what they could do to bring her here. I remember that process, but I was young, because she came in ‘57 and I was seven years old. But I remember a little bit before she came, and then the process after she came. To bring her here, everybody had to agree to the fact that she would never work here. So those visas were granted, but with stipulation.

The importance of gaining Spanish citizenship

At the beginning, I thought, “Do I want this?” When it came up that it was possible, I remember that they took a vote in their legislature, and I remember getting up at four o’clock in the morning to see if I could catch the news to see if it passed. It was very important to me to know. It was sort of the gesture that was important—to recognize that a wrong had been done—and then it was something that had been taken away from my family. And I wanted it back. I felt that it was important to take it back for all of them, but also because I wanted to respond to the gesture. I don’t believe that the sons should pay for the sins of their father. You can’t correct it or undo it, but it is something to acknowledge the fact that it happened. It was very important to me. I felt that not only did I want to recapture what was taken, but I also wanted to acknowledge the gesture. By moving forward, I felt I was saying, "Yes, this was a good gesture. This is important, and it’s important to us.” It was important to me to do it. That was the one side. On the other side, I was there the first time when I was 19 years old. I felt a very strong affinity from beginning, and I think it was cultural. I think it was that Sephardic culture that I felt when I was in Spain. So, it came at me from both sides, it was never any question to me, that I was going to move forward with it. There have been criticisms and then complaints, it took longer than it should have, for sure. But I think recognizing and acknowledging that the gesture’s been made, is a good one. And for me, when I finally finished the process, there was a sense of “Yes. This is something I wanted to do.” I have helped several people also achieve it, and that gives me pride too. I’ve met some wonderful people along the way. What’s fascinating to me is everybody’s wish and hope for this is different. It comes from a lot of different places. In many ways, it’s united a lot of Sephardics that are trying to do this.

Civil Knighthood Merit Decoration

On October 17, 2022, Doreen Alhadeff will be given a civil knighthood merit decoration. Luis Fernando Esteban, the Honorary Consul of Spain in our state (pictured above), nominated her for knighthood in recognition of her incredible work in helping Sephardic Jews gain Spanish citizenship. This process is complex and can be incredibly difficult without support; Doreen has helped many get there. Mazel Tov to Doreen on this historic honor!

See the congratulatory Lifecycle Honors page we made for her here.

The Seattle Times published an article about Doreen's path to knighthood: read it here.

The press release covering her path to knighthood is below. Click the thumbnail image to enlarge.