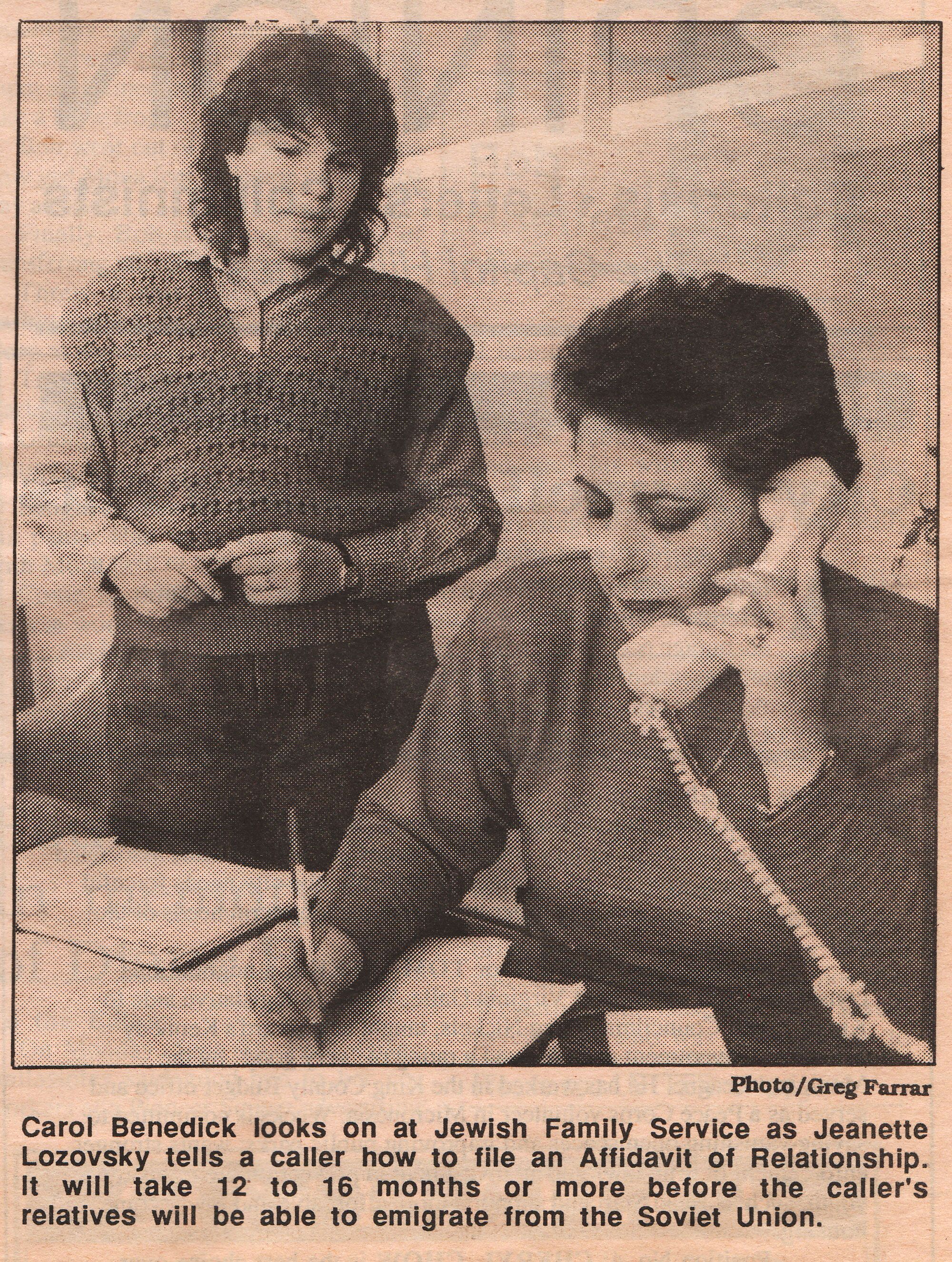

Once the doors opened for Jewish emigration in 1988, Jewish Family Service took the lead in relocating Refuseniks and other Soviet Jews in Washington State. Carol Benedick, a recent graduate in International Studies with a focus on the Soviet Union at the University of Oregon and a convert to Judaism, was the first caseworker hired to help the immigrants get settled in their new homes.

“I didn’t grow up Jewish so it wasn’t a big thing in my family growing up to be aware what was going on with Jews in the Soviet Union,” Carol recalls. “I was up in Seattle getting my Master’s degree and I saw an announcement that Jewish Family Service was looking for someone who spoke Russian. Because the floodgates had just started opening, I was hired as the first caseworker. Pretty soon after that another case worker was hired. And usually there were three of us at a time resettling all these immigrants from the Soviet Union.

“Everybody had family here. It might not have been close family,but it was family, and they sponsored them. They could not have come to the United States any other way. I spent a lot of time with each family, got to know them all pretty well. We walked the refugees through the process of getting some necessary benefits, medical coupons and health insurance, and we also provided housing and we had a warehouse where people would donate furniture. We also got them enrolled in English as a Second Language classes.

“They were very motivated. They were very educated. There were so many barriers in the Soviet Union to keep Jews from succeeding; they did a lot considering the odds against them. They were doctors and dentists and computer specialists. Their skills didn’t always translate here, so we started many skilled workers as child care employees or janitors. Many of them took classes here and moved up quickly, but it was a long process. They sacrificed their careers for their families. And they knew it, and that’s okay.

"Because of the discrimination Jews faced in the USSR, many of the immigrants had an ambivalent relationship toward their religion, though all of them strongly identified as Jews. “Most of them had lived their lives wishing that they could assimilate in the Soviet Union,” says Carol, “but the Soviets would not allow them to assimilate. Their Soviet passport had a line for nationality and theirs said Jew. They had to show their passport when they applied for jobs or university. There were some who came to the United States who loved Judaism and wanted to learn more about it and it was wonderful to have this religious freedom. So Jewish Family Service, with the help of the Jewish Federation, put on different programs to help people learn about their Judaism, their roots. There were religious school classes just for kids of Soviet Russian immigrants and many took us up on it, but most did not. For them it was finally the freedom to assimilate.”

When Carol looks at Russia today, she sees many of the same repressive tendencies she saw at the end of the 20th century, though not necessarily focused on the Jews. “I don’t trust Putin at all,” she says. “His behavior is very much like a secretary of the Communist Party. He wants power and money and I don’t think he has any scruples. I wouldn’t want to be there, but it’s great that there’s Jewish renewal going on.”