The history of the Jews in Russia is one of persecution, pogroms, and poverty. Despite promises following the revolution of 1917, the birth of the Soviet Union did little to improve the lives of the Jews. Religious practice was discouraged, if not banned outright, and organized outbursts of anti-Semitism flared up at regular intervals. The Night of the Murdered Poets, when thirteen of the most prominent Yiddish writers, poets, actors and other intellectuals were executed on the orders of Joseph Stalin, and The Doctor’s Plot, in which a group of Jewish physicians were accused of conspiring to assassinate Soviet leaders, were just two examples of official attempts decimate Jewish identity.

Ironically, despite this virulent anti-Semitism, the Kremlin had no interest in allowing its Jews to emigrate, either to Israel or to the United States. Among other reasons, the regime feared allowing Jews to leave would encourage other disgruntled groups, or even individuals, to push for the same right. While official policy allowed emigration for purposes of family reunification, such petitions were routinely refused, and those who were refused often became outcasts, losing jobs, homes, and hope. Stuck in a no-man’s land where they were unwanted but not allowed to leave, these lonely people were dubbed Refuseniks.

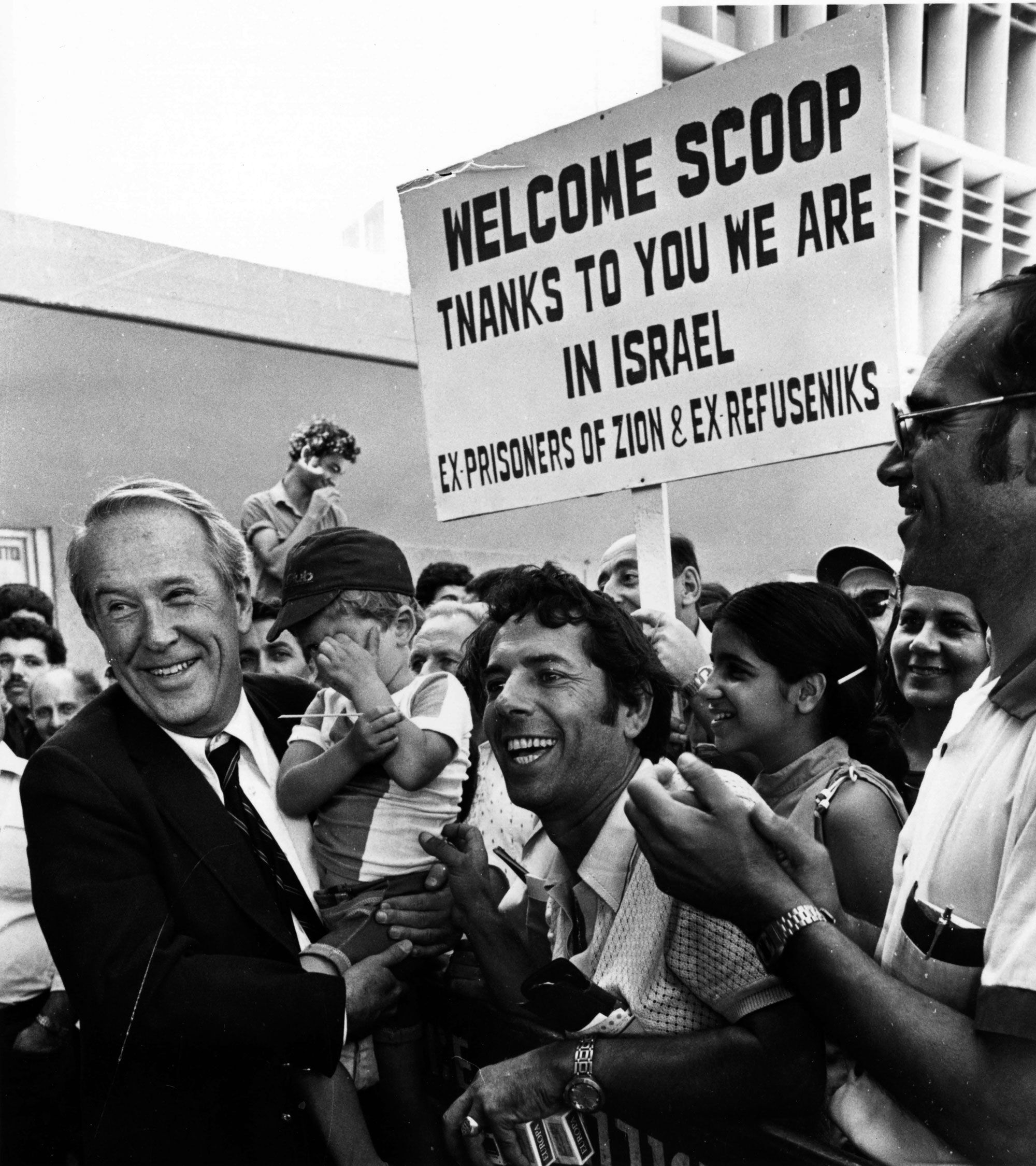

The plight of the Refuseniks attracted international attention, with Israel and the Jewish communities of the United States leading the movement to demand the right for Jews to emigrate. In Washington State, protests stretched from Seattle to Spokane, where the 1974 World’s Fair allowed protesters the opportunity to confront official Soviet emissaries who were on hand to celebrate their nation’s exhibit but weren’t prepared to meet an American Jewish community intent on practicing its right to free speech. Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., our state’s senior senator, Henry “Scoop” Jackson, sponsored the Jackson-Vanik amendment, which punished the Soviet Union and other nations that restricted their citizens’ right to emigrate.

Refuseniks Podcast

Player not loading? Listen to the podcast directly on SoundCloud.

"The Soviet Jewish Experience: Washington State Stories" looks at four Seattleites whose lives were impacted by the Kremlin's restrictive emigration policies prior to the fall of the Iron Curtain. Seattle Symphony violinist Mikhail Shmidt and University of Washington professor Gregory Korshin grew up in a Russia where institutional antisemitism meant Jews would always be second class citizens but would rarely be allowed to leave for less discriminatory countries. In Spokane, high school student Beth Huppin led protests against the Soviet delegation at the 1974 World's Fair, while in Seattle, Jewish Family Service caseworker Carol Benedick helped resettle immigrant families once the floodgates opened in the early '90s. This special podcast is part of Washington State Jewish Historical Society's local companion piece to the national traveling exhibit "Power of Protest: The Movement to Free Soviet Jews" from the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia.

What follows are just a few of the stories of Washingtonians who helped lead this fight for freedom, and of the Soviet immigrants who have made Washington State their home.

The Soviet Jewish Experience: Washington State Stories is generously supported in part by:

Washington State Jewish Historical Society is dedicated to discovering, preserving, and disseminating the history of the Jews of Washington state and promotes interest in and knowledge of the life, history, and culture of the Jewish people and communities through publications, exhibits, displays, speakers, tours, and performance.