My parents had managed to leave Lithuania in 1939 and come to America, where my mother had an uncle in New York who sponsored them. My parents had just married, and 1939 was the year of the New York World’s Fair, so they thought that the trip might just be an extended honeymoon, but they also knew that they were unlikely to return any time soon. The German invasion and occupation of Lithuania came two years later in 1941, and it became clear that they’d never go back. Everyone else in their families stayed behind and would be murdered. I remember my parents placing ads in The Forward, trying to find if there were relatives who by some miracle had survived. That was how I learned about the Holocaust. I was born in New York City. My parents were refugees and they had settled on the Lower East Side. We moved to Queens when I was three years old, but they still identified with the old neighborhood. We were still going there to shop, to the Essex Street Market. It was just our nuclear family: my parents, my sister and me. I never had a sense of extended family, and to this day I have trouble identifying relatives. That’s a small price to pay, but it’s an example of where the history affects people’s thinking. It should be automatic to know what an aunt is. It’s something I never experienced firsthand.

There was nothing to go back to. Things were very bad already when they left in 1939 and continued to get worse even before the Nazi invasion. My father, a physician, had attended medical school in Montpellier, France, and returned to Lithuania after completing his internship and residency in Geneva. They lived in the Jewish quarter, and my father would be pelted with stones when he crossed a bridge to get to the hospital. When my mother’s uncle urged them to come to America, my father was reluctant. But my mother said, “Well, look at what it’s like when you go over to work, you get hit by stones. I think we should consider that.” She’s the one who motivated the move. They came with some possessions: a few wedding items, several suitcases, but not much more. The uncle helped get them established on the Lower East Side, and my father worked in a Jewish nursing home at first, the Bialystoker Jewish Home for the Aged on the Lower East Side. Later he worked at Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx and at the Willowbrook Hospital on Staten Island.

When I was planning a trip to Israel, my mother put me in touch with someone who had left her hometown in Lithuania and settled in Israel. It was the first time I met one of my mother’s childhood friends. She told me, “Your mother’s house was the only non-kosher house.” When I came home with that, my mother was very embarrassed. She explained that they were very integrated with the community. Her father was president of the bank of the small town of Rietevas, and her mother was the midwife. In New York, we didn’t keep a kosher home. My sister is six years older than me and started school when we were still on the Lower East Side, so my parents sent her to a yeshiva because they didn’t think the public schools would be good. When I began school, we were already in a middle-class neighborhood in Queens, with excellent public schools. I didn’t receive a Jewish education, or even go to Hebrew school. We belonged to a synagogue, of course, and the prayers are in my ears.

Relationship with family and music

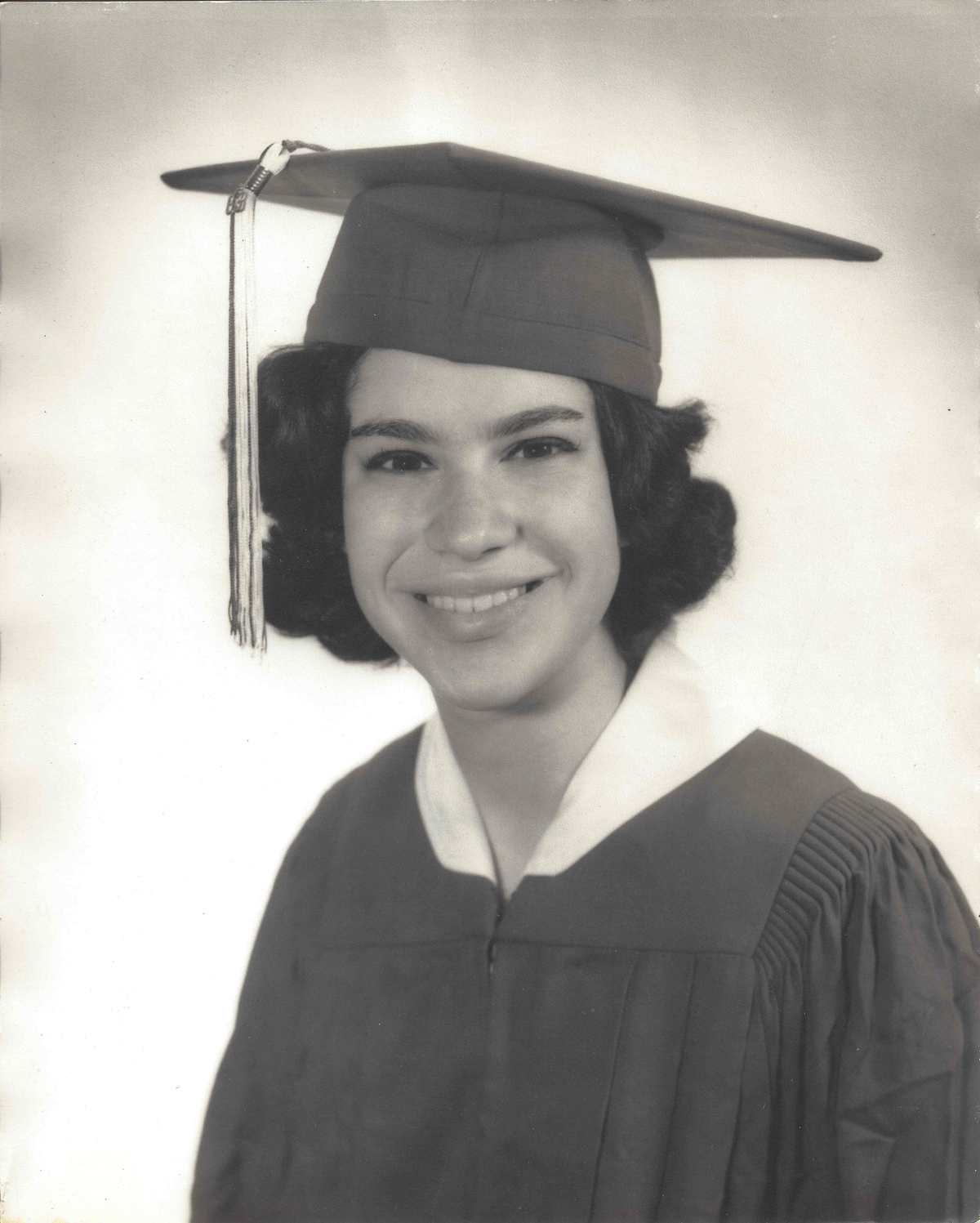

My parents had to struggle in a new country and learn the language, really scraping things together as best they could. My mother was a pianist, but she couldn’t make a career as one in America. My father was challenged to establish himself as a physician. They were struggling, and the last thing they wanted for their children was to choose professions that didn’t offer financial security. My father always took his two children to the hospital with him and he would introduce us by saying “two daughters, two doctors.” My sister followed in his footsteps and became a successful and widely-admired doctor. As for me, I would faint at the sight of blood, so I didn’t think that medicine was going to be a very good match. I wanted to play the piano. My mother felt that she would be the best piano teacher for me, but when we had lessons it became obvious that this wasn’t working out. Parents aren’t necessarily the best teachers, even if it’s a driving lesson. When I was sixteen, I enrolled myself in the pre-college division of the Manhattan School of Music. I was obsessed with becoming a pianist, practicing 8-10 hours a day, and chose to attend a conservatory rather than an academic college so that I could devote myself to playing. I went to Manhattan School of Music for my bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and then I did a Ph.D. in performance. But I also took my parents’ caution to heart, knowing how uncertain the chances were of making it solely as a performer. With my Ph.D., I took an academic position that also gave me opportunities to play.

My Ph.D. dissertation had nothing to do with the Holocaust or the work I’m doing now. It was a study of the music of Carl Nielsen, a Danish composer. So that was my project. I met my husband at the time that we were both in graduate school and living on fellowships. You can’t go very far in New York on fellowship money. In 1977, the year we got married, both of us were looking for academic jobs, and I was offered one at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. I took the position, and David found something while we were there. We stayed there longer than we’d expected and became involved with Lexington’s Jewish community. Many members of the Jewish community, like us, were academic and professional transplants from larger cities, and the community felt like an oasis of cosmopolitanism. At the same time, we discovered how Jewish life in the South was different from what we’d known.

After we’d been in Kentucky for about ten years, David’s parents in Philadelphia developed serious medical issues, and as an only child he felt he needed to be closer to help. He found a find a position back East and I tried too, but the academic job market in music was practically non-existent and we ended up commuting between Lexington and Philadelphia. When David’s mother died and his father seemed to be okay for a while, David was offered a wonderful position in Seattle. It was 1990, and he accepted it with the understanding that I’d try to relocate – but in the meantime the commute became even longer. When I moved to Seattle at the end of the 1996-97 academic year 1997, I made a commitment to making Seattle our life.

I wanted to see what I could do that would make a difference. In all my years of performing and being a music educator, I always felt that music had to reach a greater cause of humanity. I didn’t feel music was for entertaining. I felt that I wanted to do something that would make a difference and that would speak to me and use my art in a way that would have a voice. Around that time I was drawn to the music of the Czech composer Leos Janacek. I began studying and performing his music, and produced a CD recording of his complete piano works. Discovering Janacek and his milieu, I learned more about the Terezin concentration camp, about 35 miles north of Prague, and about how the Nazi camp tried to use it as a propaganda “model ghetto.” It was a gateway to Auschwitz and other death camps, but its prisoners included important Jewish artists who were allowed to compose and perform music.

Sowing the seeds of Music of Remembrance

I became fascinated with the concerts and the music that was performed at Terezin, and I learned about the composers who created incredible works even under those conditions. These were the seeds of Music of Remembrance when I moved here in 1997, and sought the advice of Gerard Schwarz, the conductor of the Seattle Symphony, who was also deeply involved in the Jewish community. I summoned the courage to ask if he would meet with me, so I could share my ideas and seek his advice. I said, “I’m new to the community and this is my idea. I want to establish a concert series: one concert to mark Kristallnacht, one to mark Yom HaShoah.” He responded: “It’s a great idea. My advice to you, since you’re working with serious performers and you want these concerts to be taken seriously, put it in Benaroya Hall.” Benaroya Hall was about to open that fall. “We have this great concert hall and the recital hall is fabulous and that’s what you should do.” And then he added, “All you can lose is money!”

I filed for MOR as a legal 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, and we needed a board. I knew half a dozen people, and I asked them: “Just help me do this.” They didn’t know how this organization would fare, but they took a leap of faith. Our budget for the first year’s two concerts was about $20,000. My husband David and I worked for free. We didn’t advertise except by printing flyers for friends to put up, and telling the synagogues and people we knew by word of mouth. The office was in my study in our home. The phone rang at any time of day, and I took every call. We didn’t have the tickets printed until we had sold the seats, and then we’d go to Kinko’s and print out a few pages and cut off the ticket stubs. For the first concert I didn’t know if we were going to have 100 people or 500. We had a full house. After that concert, people called me, saying “That was spectacular, I’d like to volunteer, I’d like to help.” In fall 2005 we moved out of my study into an office space. And that’s where we are now in Magnuson Park, where the city has a complex of offices that it rents to non-profits. We hired our first employee, and since then we’ve grown and developed the organization.

The significance of their work

Besides performing music from the time of the Holocaust, our mission from the beginning has included commissioning new works inspired by the Holocaust. We’ve made a point every year to commission at least one piece telling a story. These stories have given voice not only to Jews, but also to free-thinkers, political dissidents, Roma, gay people, women, children. Now that we’re celebrating our 20th season, we have commissioned about thirty works, and we have others in the pipeline. Our commissions are varied musically. They include chamber works, song cycles, choral music, film scores, and even two fully-staged and costumed operas. A third opera is in the works for 2019. We believe we honor the Holocaust’s moral lessons by looking at the impact of war and persecution on different groups excluded because of their faith, ethnicity, gender or sexuality. For this year, we’ve commissioned a new work about the wartime internment of Japanese Americans. We’ve always produced at least two major concerts each year at Benaroya Hall, and we try to keep tickets affordable, especially for the younger people we want to reach. Every January for the last four years, we’ve added a free community concert on or around International Holocaust Remembrance Day to mark the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. Since 2015 we’ve also reached out with an annual concert in San Francisco. We’ve grown and evolved in so many ways, and faced many challenges, but it’s always been a labor of love.

Despite how our programming has grown, we’re still a small organization. We have three full- time employees, including me as artistic director. There’s an administrative specialist who manages the office, and a development professional. Our musicians aren’t MOR employees. Most of the instrumentalists are drawn from the Seattle Symphony, and we contract with them for engagements in our concerts. Besides their amazing talent, they’re very loyal and strongly committed to our mission, and many of them constitute what amounts to an unofficial core ensemble that’s been with us from the beginning. We also bring in top soloists nationally, and sometimes internationally, but we call on local talent whenever we can. We try to nurture fresh talent, and we’ve established the David Tonkonogui Memorial Award, in honor of a cherished colleague, for young musicians interested in the Holocaust’s musical legacy.

I emphasize using the best musicians I can find. Many of them are Jewish, but not all. Several are Russian emigrés who left the Soviet Union in the late ’80s, and our music has special resonance for them. They could not play Jewish music at home, and they couldn’t practice Judaism, so our programs have an element of self-discovery for them. Similarly, for the composers we commission, it’s not about whether they’re Jewish, it’s about their affinity for the subject matter and the match of their musical ideas and style.

We’re very proud of our collaboration with composer Jake Heggie – not Jewish – who is one of the most admired opera composers of this century. His first commission for us – “For a Look or a Touch” – was a musical drama that illuminated the persecution of gays in the Holocaust. Jake, a gay man, identified strongly with the subject and wrote deeply from his heart. The work was based on the story of two idealistic young lovers – Jewish, by the way – whose lives and love were shattered under the Nazis. We continued to work with Jake on other projects together, culminating in the opera “Out of Darkness.” We premiered it in 2016, and since then it has been going around the world. This is exactly why our commissioning program is so important. These are stories that need to be told. For example, Heggie’s “Another Sunrise,” which we premiered in 2012, is about the amazing true story of Krystyna Zywulska. Born Sonia Landau to Jewish parents, she escaped from the Warsaw ghetto, changed her name and worked for the Polish underground resistance. She was captured by the Gestapo and sent to Auschwitz as a political prisoner, not as a Jew. In Auschwitz she wrote poetry and songs that circulated secretly in the camp and became anthems of defiance. The work looks at the decisions she was forced to make in order to survive and compels us to reflect on the cost of wrestling with the ghosts of memory.

When we started 20 years ago, much of the music – and stories – of composers who were murdered or banned was little known, and we were pioneers in bringing some of these beautiful and important works back from obscurity. More of this music is being performed now, and we’re proud of the role we might have played in the revival. To just continue performing Holocaust era music by composers that were murdered is noble, but others could do it too. What Music of Remembrance has done is to go beyond that, to commission new work. This truly is a legacy of Music of Remembrance, to tell stories that illuminate, stories of hope and courage and inspiration. Our larger and unique impact, especially over the last decade, has been through the commissioning of new works that tell essential stories and connect the Holocaust’s urgent lessons to today’s world. These works travel around the world, but we take great pride that they’re all launched here in Seattle and involve Seattle’s vibrant cultural life and Jewish community.

After Pearl Harbor, the United States removed more than 120,000 people – most of them American citizens – from their homes and incarcerated them because of their Japanese ancestry. This story and its lessons are particularly timely for us today. We’ve commissioned the French-born American composer Christophe Chagnard to create a work for us on this chapter of history that we’ll premiere in May 2018. Christophe is known here as the leader of the Northwest Sinfonietta for 24 years, and now as the conductor of the Lake Union Chamber Orchestra. As a composer he’s drawn to music addressing social issues, and recently he created a powerful work on climate change. He’s titled his new work “Gaman,” a Japanese term that refers to the struggle to endure the unbearable with patience and dignity. I’ve worked closely with Christophe in shaping the piece. He’ll incorporate visuals using paintings and drawings created in the Minidoka camp by artists who were imprisoned there, and he’s crafting a libretto based on their diary entries to portray the experience through their own eyes and words. The music will merge Western instruments with a traditional Japanese Fue flute and Taiko drum. We’re very excited about this work and believe it will convey a message that has special importance at this moment.